Sogo bò, the Bamanan masquerade

by Elisabeth den Otter

From September 2001 till September 2002, I spent a year doing more in-depth research, together with Mamadou Kéïta, my Malinese counterpart. The aim was to study and document the traditional masquerades of the Bamanan in the area of Ségou: the history, function and meaning of the puppets/masks, as well as the accompanying music, songs and dances, from an anthropological perspective and considering the social context and the changes that occur therein. The project was coordinated by N.G.O. 'Alphalog' (Ségou). The Royal Tropical Institute (Amsterdam), where I worked as curator of the Department of Ethnomusicology, paid my salary and my travel expenses. The expenses in Mali, including the production of books and video documentaries, were paid by the Prince Claus Fund (The Hague).

The masquerades of a number of villages in the area of Ségou were studied in their social context, in order to document and safeguard this important aspect of the cultural patrimony of the Bamanan. To achieve this, a number of masks/puppets have been inventoried, classified and described. In view of their importance, the songs which accompany the masks/puppets have been analyzed as a form of narration. The social function and the organization of the masquerades by the youth associations was also studied.

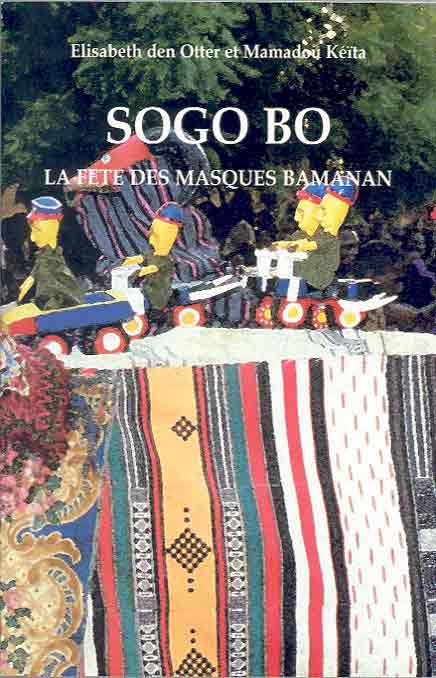

The research resulted in the publication of the book 'Sogo bò. La fête des masques bamanan', by Elisabeth den Otter and Mamadou Kéïta, in 2002. It numbers 132 pages, with 78 color photographs, and was printed by Imprim Color (Bamako): 700 copies in French and 300 copies in Bamanan. A number of books were distributed free of charge to libraries, youth centers, cultural associations, research institutions, and the villages implicated in the research. The remaining copies will be sold through the National Museum, libraries, large hotels, etc; the proceeds will be used by Alphalog for future cultural projects.

Two video documentaries were produced as well, in cooperation with CESPA (Centre de Services de Production Audiovisuelle), Bamako:

-- 'Kirango sogo bò', on the masquerade of Kirango, including the social context such as the activities of the youth association which organizes the masquerade. (40 minutes)

-- 'Pelengana jiritigèw', about a family of blacksmiths who also carve puppets and masks; some masks of the masquerade of Pelengana are shown in action. (10 minutes)

A limited number of VHS-copies of the videos have been distributed to the villages and the research institutions directly implicated in the research.The original material (slides and videotapes) has been deposited with the National Museum in Bamako, accompanied by descriptive lists and copies of the book in French and Bamanan.

Collective memory

An interesting aspect was the relation of the actual (non-religious) masquerade with the old initiation societies of the Bamanan: Ntomo, Kòmò, Nama, Kònò, Ciwara, Kòrè. During the masquerades, we see the Ntomo and Ciwara societies appear in the form of masks, the Kòmò society in the form of row dances, and the Nama society in the form of a puppet made of straw. Faaro, the water deity, is represented as a rod puppet. These survivals may be seen as a 'collective memory' of animistic rituals now forbidden by Islam.

The Ntomo mask

The Ciwara masks

Sogo Nama

Faaro, the water deity

The future

Another aspect which interested us was the future of the masquerades: will they disappear, change into 'folklore' which has little relation to village life, or adapt to modern times? Reason for optimism was a mask made by Modibo, a young man from Pelengana, at his own initiative and expense. It represents an antelope, beautifully painted, with small fish and antelopes on its horns and decorated with a sun, a moon and a star. Small lights attached to it light up at night. Its name is 'Madanitile' (the Sun of Madani), as it is named after Modibo's father, a famous sculptor in his days.

Modibo with 'Madanitile'

This 'total theater', where various expressive forms come together and in which the public plays an active role, expresses the values of society and transmits them to the next generation. It is a way of continuing tradition, and an important means of cultural identity.

Because of factors such as modern education, ubanisation, migration, influence of Islam, and lack of (financial) means, many villages do not perform their masquerades anymore. But there are also more recent influences, such as tourism, that contribute to changes in the masquerade.

More about puppetry

Home